Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) is among the 20th century’s most groundbreaking and significant paintings. This masterwork, which was painted by Pablo Picasso, a Spanish artist, represents a turning point in both his career and the evolution of modern art.

It not only questions accepted ideas of representation, but it also marks the beginning of Cubism, a revolutionary movement that would go on to influence Western art for many years. This examination will look at the painting’s formal components, historical background, impact, and how it fundamentally changed how the human form is portrayed as well as how art and reality interact.

Context: A Break from Tradition

Understanding the background in which Picasso produced Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is essential to appreciating the piece to the fullest. Europe saw significant upheaval in the early 20th century. Modernism was pushing the limits of what was deemed artistically acceptable and challenging conventional forms of art with its many subgenres and avant-garde movements. Artists were experimenting with fragmented shapes, abstraction, and new ways of representing space instead of representational art.

In 1905, Picasso started experimenting with what would later be referred to as his “Blue” and “Rose” eras. These periods are marked by emotionally charged, introspective works with melancholic tones and symbolic motifs.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, on the other hand, marks a significant break from the figural realism that had defined his previous pieces. His exposure to African art, Iberian sculpture, and the work of fellow artist Georges Braque, who was also starting to experiment with new approaches to form and space, were probably some of the elements that contributed to this change.

Picasso’s preoccupation with the complicated connections between men and women in Paris’s district of Avignon served as the inspiration for the painting itself. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’s composition, subject matter, and style all reference these topics, but Picasso reinterprets them in a way that was both daring and unnerving to viewers at the time.

Subject Matter: The Confrontation of the Female Figure

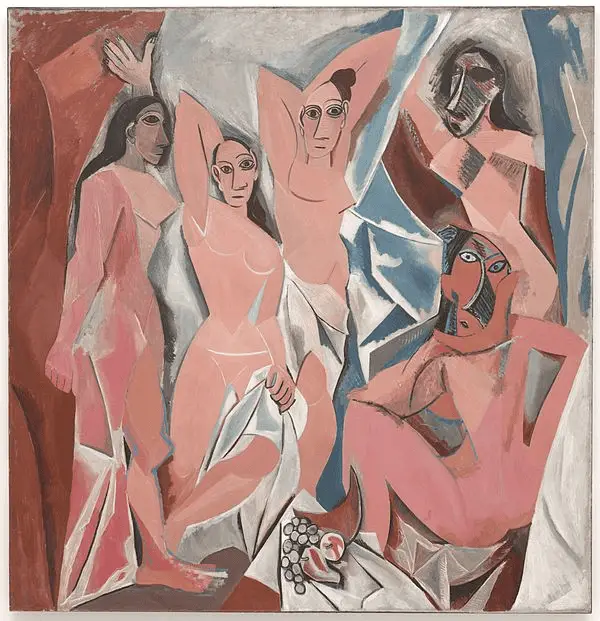

Five women form the composition’s focal point. The viewer is given a sense of confusion and difficulty by the variety of positions and arrangements in which these figures are portrayed.

The women are neither romanticised or idealised as has historically been the case in academic painting. Picasso instead depicts them in a bare, nearly savage way. The viewer’s perception of the feminine form is disturbed by the manner the women’s bodies are presented—they are broken up, warped, and deformed.

Despite what is depicted in the picture, passive voyeurism or passive consumption are not its themes. It is an aggressive confrontation instead. The figures’ sharp, abstracted shapes and somewhat combative gazes give the impression that they are immediately challenging the viewer. A complex power dynamic between the artist, the model, and the viewer is suggested by their intense and steady gazes.

Furthermore, Picasso presents themes of objectification and commodification through the brothel, but in a unique way. The women in the picture have been drastically redesigned as strong, multifaceted individuals who defy the conventional roles that have been ascribed to them in both art and society, making them more than just passive objects of male desire.

Formal Elements: Cubism and Abstraction

Picasso’s inventive use of shape, space, and perspective distinguishes this painting from conventional representations of the human form. It is regarded as an early example of Cubism, a style Picasso would later develop in partnership with Georges Braque.

Picasso departs from linear perspective to use a fragmented, multi-perspective approach, in which the women’s bodies are distorted and broken up into geometric shapes and planes that appear to flatten the space within the composition. Instead of presenting a cohesive, unified perspective, Picasso produces a startling effect by utilising multiple viewpoints at once.

The Cubist concern in showing an object from multiple perspectives to provide a more comprehensive grasp of the subject is reflected in the figures’ sharp angularity and lack of a single, fixed perspective.

Picasso’s use of jagged, sharp lines in the left half of the canvas suggests a Cubist approach of the body, while the figures in the right half have a more angular, mask-like appearance that is reminiscent of African art. The figures’ abstraction is enhanced by the use of flat planes and the lack of conventional shading methods. The artwork deviates even more from traditional ideas of beauty and depiction due to its use of stark, simple forms and lack of actual depth.

The abstraction of the women’s faces is very remarkable. Some are completely reduced to geometric shapes, while others are depicted as flat, mask-like shapes with exaggerated features. These depictions of faces show the influence of African masks, which Picasso had seen at the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris. Picasso was greatly influenced by African art, which placed a strong emphasis on abstraction and stylisation, while he attempted to reject Western art traditions.

Color and Texture: Creating Tension

Picasso makes effective but restrained use of colour in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Areas of pale, nearly sickly greens and blues contrast dramatically with the palette’s warm tones, which are mostly earthy oranges, browns, and reds. These hues add to the painting’s overall eerie atmosphere. The sensual character of the subject matter is further emphasised by the warm colours, especially the reddish tones, which may arouse feelings of carnality and the flesh. However, when the observer is faced with the figures, the cooler hues—especially the blues and greens—introduce an isolating or unnerving quality that adds to their discomfort.

The painting’s texture is also quite important. Picasso’s apparent and frequently unpolished brushstrokes give the painting a rough surface that heightens the sensation of aggressiveness. The figures appear more shattered and less polished, as if the paint is straining to capture the scene’s ferocity and disorder. The work’s emotional intensity and rejection of the smooth, idealised shapes that had defined traditional representations of the nude throughout art history are further reinforced by this raw roughness.

The Influence of African Art and Iberian Sculpture

Picasso’s exposure to Iberian sculpture and African art was one of the major influences on Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, as was previously mentioned. Picasso and many other European artists were captivated by the aesthetic breakthroughs of African and Oceanic art in the early 20th century. In sharp contrast to the naturalism that predominated in Western art, these pieces frequently emphasised stylisation, abstracted forms, and reduced shapes.

The women’s mask-like faces in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon are a clear allusion to African masks that Picasso saw while visiting the Musée d’Ethnographie. Picasso used these masks’ abstracted, geometrised characteristics, which he appropriated for his own artwork.

His interest in Iberian sculpture, which prioritised geometric abstraction and prioritised volume and mass over realistic detail, is also reflected in the angular, blocky depiction of the human figure.

Picasso was able to transcend the Western tradition of portraying the human body as an idealised object of beauty by combining these inspirations. Rather, he adopted a fresh, more disjointed, and emotional style that enabled him to portray intricate feelings and mental states.

Reception and Legacy

It was greeted with surprise, bewilderment, and criticism upon its initial display in 1916. The piece was viewed by many commentators as an uncontrollable and disorganised attack against conventional beauty. It was challenging for viewers used to the principles of classical art to comprehend the painting’s radical abstraction and unnerving depiction of the feminine figure.

When Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was first exhibited in 1916, it was met with shock, confusion, and criticism. The piece was viewed by many commentators as an uncontrollable and disorganised attack against conventional beauty. It was challenging for viewers used to the principles of classical art to comprehend the painting’s radical abstraction and unnerving depiction of the feminine figure.

Over time, however, the significance of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon became more widely recognized. It is now considered one of the foundational works of Modernism, a symbol of Picasso’s genius and his ability to push the boundaries of representation. The painting’s invention provided the framework for Cubism, which would go on to change the art world.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon also foreshadowed coming trends in abstract painting and the dismantling of conventional ideas of gender and sexuality that would be at the heart of feminist art critique in the future.

Conclusion

A turning point in the development of Western art can be found in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Picasso expanded the possibilities of depiction by rejecting academic painting conventions and embracing abstraction. The artwork presents the viewer with a disturbing and radical rethinking of the human body through the use of fractured form, numerous viewpoints, and a rejection of idealised beauty. By referencing Iberian sculpture, African art, and modern ideas of power and sensuality, it is also a piece that is intricately entwined with the artistic, political, and cultural currents of the day.